As Serrat sings in one of his songs, “De vez en cuando la vida” (“Every Once in a While, Life”):

“Every once in a while, life has coffee with me

And looks so beautiful it’s a joy to see.

She lets her hair down and invites me

To step onto the stage with her.”

The truth is that this time, life not only had coffee with me but also a good amount of garagardoa and sagardoa—words that, for those of us who don’t speak Euskara, mean beer and cider, respectively.

But let’s get to the important part.

Last Thursday, October 28, I had the pleasure and honor of presenting a screening of John Feldman’s documentary film “Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis Rocked the Boat and Started a Scientific Revolution” at the Aita Mari cinema in Zumaia.

This event was part of the “Parallel Activities” organized as a complement to the series “Cooperation, an Evolutionary Force. Lynn Margulis, 10 Years Later,” an effort to decentralize the main events, most of which are being held in Barcelona.

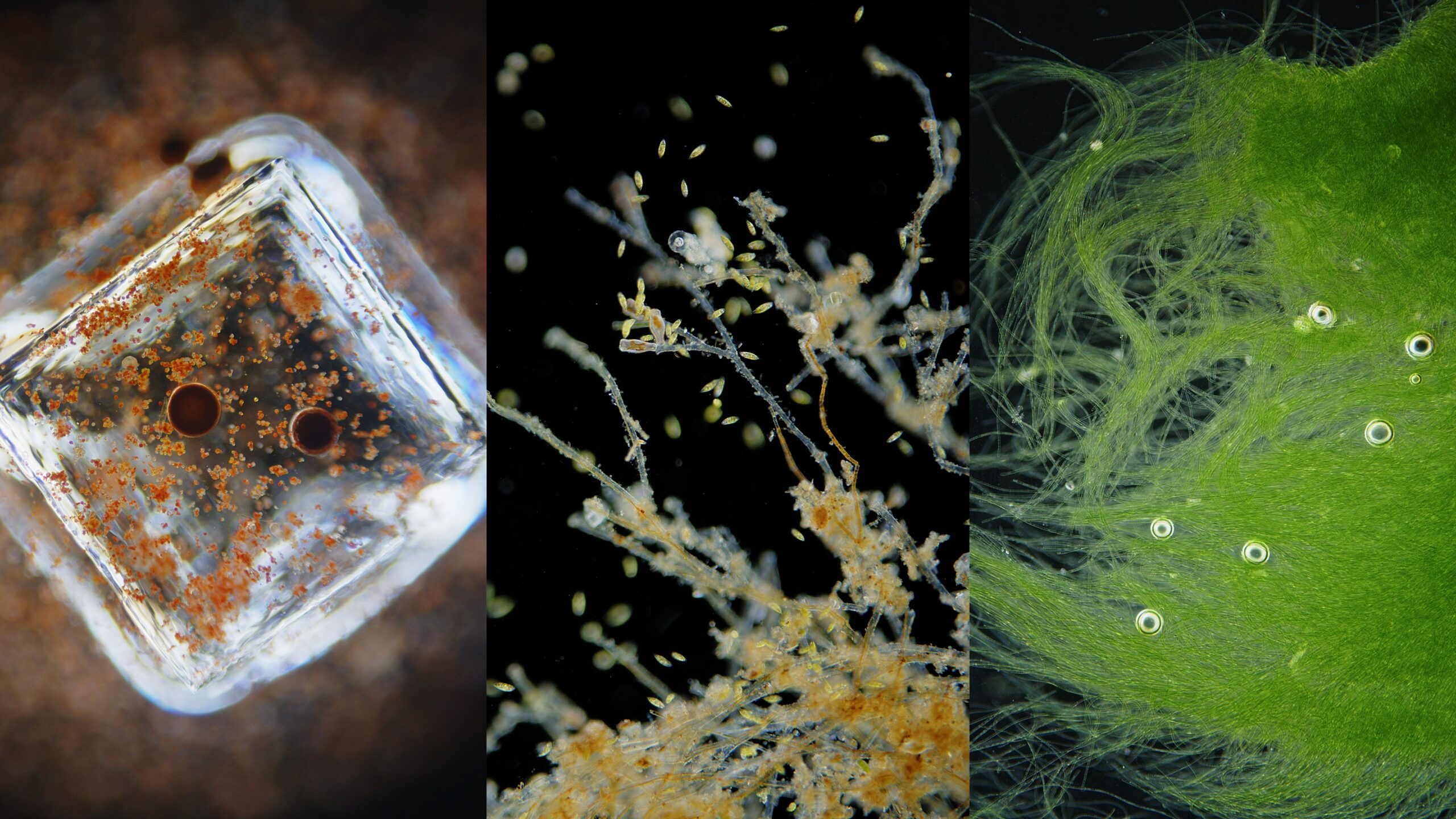

For two and a half extraordinary hours (the length of the film), more than 60 people had the opportunity to learn about Lynn Margulis—some for the first time—as well as her groundbreaking scientific theories on the evolution of life on our planet (you know, endosymbiosis, serial endosymbiosis, and symbiogenesis).

It doesn’t surprise me that for biologists like myself, or for those studying other natural sciences, Lynn’s proposals are inherently fascinating (I won’t get into the implications they have for our understanding of biological evolution here). And her figure is, of course, incredibly compelling. However, what does surprise me (though only to a certain extent) is the interest she sparks among people more associated with the humanities—especially in sociology.

I am convinced that this interest arises from the proposal of a scientific paradigm shift—one that can be applied to sociology just as easily as it can to biology. And this, in fact, has been happening for a very long time.

This was the case with the “modern synthesis,” better known as “neo-Darwinism,” an evolutionary theory that, when applied to social structures, has been used to justify the exploitation and competition characteristic of the ruthless capitalist system that has dominated—and continues to dominate—social relations at every level, from individuals to corporations and nations.

Lynn’s theories, which suggest that evolution is more about cooperation (even though she personally avoided using that term in a biological context) than competition, align perfectly with the paradigm shift that a portion of society is now advocating for (I was about to write a significant portion, but that might be overly optimistic).

This paradigm shift calls for a radical change in our relationships—with each other, with the other living beings we share the planet with, and even with the planet itself.

The Climate Summit currently taking place in Glasgow is a clear example of how necessary this shift is. It is also proof that the concept of “survival of the fittest” remains deeply ingrained in our society. That is precisely why so many Climate Summits have been necessary, and yet their results have been, at best, insignificant. And it’s not hard to see why—just before the Glasgow Summit, the G20 meeting took place, bringing together “the strongest.”

I believe Serrat—again, Serrat—captured this dynamic perfectly in another song, “Algo personal” (“Something Personal”):

“… The hitmen never miss an opportunity

To publicly declare their commitment

To fostering a dialogue of open relaxation,

Which allows them to find a preliminary framework

That guarantees minimal conditions

To create the mechanisms

That will drive a solid and capable starting point

From East to West and North to South,

Where they can establish the foundations of a friendship treaty,

That will help lay the groundwork

For a platform on which to build

A beautiful future of love and peace.”

But let’s get back to the screening in Zumaia.

One of the most special aspects of this event was that, for the first time, the film was shown in its original English version—with Euskara subtitles!

Collaboration and cooperation were the two key elements that made this possible. Collaboration between institutions such as the Zumaia City Council (Zumaiako Udala), the Basque Coast Geopark (Geoparkea Euskal Kostaldea), the Zumaia Women’s House (Zumaiako Emakumeon Etxea), and the Zumaia Naturalist Group (Zumaiako Natur Taldea); and cooperation between individuals, like the team of translators led by Inaxio Manterola, Alex Oliden, and Gontxalo Torre. Thanks to their work, Lynn’s theories and legacy could reach more people—and in their own language.

While in Serrat’s song, the “types” he refers to and I have “something personal” in a negative sense, the “types” I just mentioned in Zumaia and I also have “something personal,” but of the opposite nature. It is something personal rooted in admiration for their ability to collaborate, to work together in a completely selfless way on a project that aimed—and I hope succeeded—in offering new ways of thinking. And new ways of thinking, after all, are essential for the evolution of ideas.

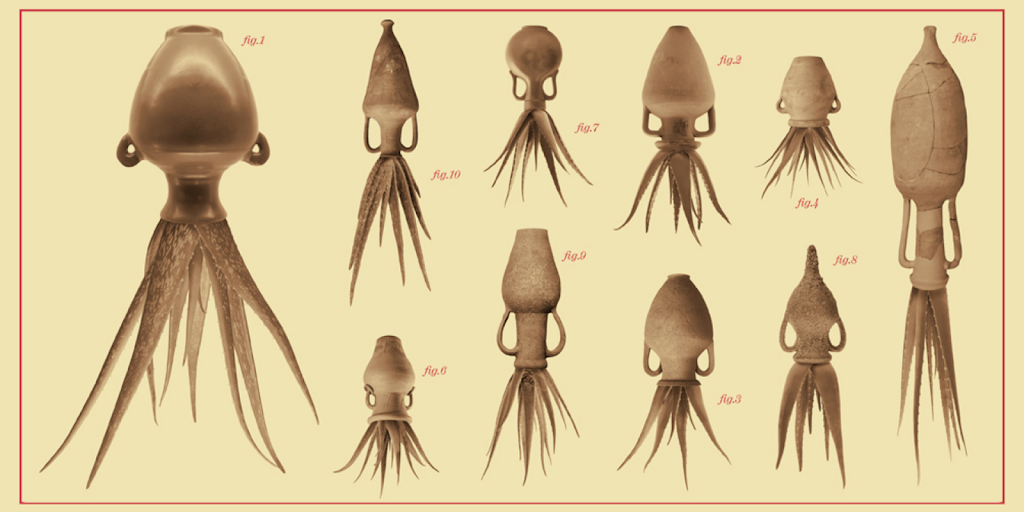

And to top it all off—what better setting than the famous Flysch of Zumaia to talk about evolution? This extraordinary geological environment, now protected under the Geoparkea designation, preserves a 110-million-year record of our planet’s history—one that can be read like a book. Here, with the guidance of Geoparkea experts, it is even possible to see the K/Pg boundary (Cretaceous/Paleogene boundary), a thin “black line” that marks the transition between the Cretaceous (K) and Paleogene (Pg) periods, dated to around 65 million years ago. This line is characterized by an extraordinary concentration of iridium, a remnant of the Chicxulub asteroid impact in the Gulf of Mexico.

For those interested in the full program of activities organized to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Lynn Margulis’ passing (1938–2011), you can find it on our website, Science into Images.